Since the introduction of hydrated calcium silicate-based cementum into endodontic treatment, methods of living pulp preservation have gained increasing popularity. There are several therapeutic approaches to crown pulp exposure, and pulpotomy is theoretically one of these therapeutic possibilities. In this article, we will describe the practical aspects of this method in two clinical cases and also compare it with pulpotomy.

introductory:

Live pulpotomy is common in the treatment of deciduous teeth and it is a well-recognized method of treating caries with pulpal involvement. In addition to removing decayed and softened dentin, it is necessary to remove the affected portion of the pulp (e.g., irreversible inflammatory pulp) as well as to preserve uninvolved pulp tissue. In cases of traumatic pulp exposure in anterior teeth, up to 7 days after the trauma has occurred, a similar approach can be used to preserve pulp viability. In such cases of exposed pulp, the inflammatory changes that can be seen on histologic examination are limited to the upper 2 mm of pulp tissue. In performing the severance, the exposed pulp tissue is separated at an appropriate height and covered after hemostasis, and accordingly, a number of different pulp-capping agents have been suggested for clinical use. The therapeutic goal is to protect a portion of the crown pulp or at least the root pulp from becoming active, as well as the integrity of the periapical tissues. In teeth with underdeveloped roots, this treatment makes root atresia (increase in length and canal wall thickness) possible.

In contrast to pulpotomy, only a portion of the pulp tissue is removed during a vital amputation or pulpotomy. It was used 100 years ago as a treatment for localized pulpitis. A common form of pulpotomy is to cut the pulp at the root canal filling, which is also easier to perform. In principle, the pulp can be severed anywhere within the root canal or pulp chamber. It does not matter whether the root development is complete or not. The key to the prognosis is that the remaining tissue is able to initiate the restorative process. Clinically, it is important to be able to stop the bleeding well after pulp isolation. Failure to stop the bleeding indicates irreversible inflammation of the remaining pulp tissue.

Clinical Procedures:

After local anesthesia, the pulp is wetted and opened, and the involved pulp tissue is removed gently and as much as possible. In order to separate the pulp at high speeds, it is necessary to use an emery turning needle under cooling. The use of hand tools or low-speed ball drills is not recommended as they can cause pulp contusion or leave jagged wounds. An intracoronal diagnosis is then performed to assess the condition of the pulpal tissue and to ensure that a proper initial clinical diagnosis is made and treatment is planned. To stop bleeding, saline, aluminum chloride or sodium hypochlorite solutions are recommended. The pulp capping agents used to cover the pulpal section are calcium hydroxide preparations, which are the gold standard, but their use has several side effects, including: sterile pulp necrosis on the contact surfaces, brittleness of the tooth’s hard tissues and the consequent increase in the risk of fracture of the tooth, or cavitation effects due to the absorption of the preparation. As a result, mineralized trioxide agglutinate (MTA) is gradually replacing calcium hydroxide as the pulp capping agent of choice. It has yet to have any negative effects other than causing tooth discoloration. Since the end of the nineties, calcium hydrosilicate-based cementums, which are free of discoloring agents and use zirconium oxide as an x-ray contrast agent, have been used in dentistry. The use of MTA-based preparations to cover pulpal sections is still recommended because their success rate in treating reversible pulpitis can be 80 to 90 percent after two years. After pulp capping, clinical crowns should be sealed to prevent bacterial microleakage from occurring during the same course of treatment.

Case presentation:

History and examination:

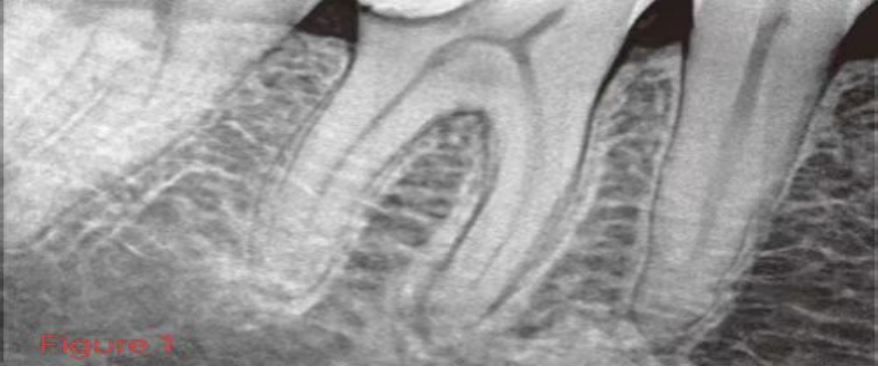

Patient, female, 30 years old, was referred for root canal treatment of tooth #46. The patient was asked to deny the general medical history. Examination at the first visit revealed that the pulp had been exposed in spots during treatment for deep caries and the tooth had been temporarily filled. The patient was asymptomatic and the clinical presentation was unremarkable. Pulp vitality testing was sensitive to thermal and electrical stimulation and negative to percussion. Imaging showed a marginal discontinuous filling on the clinical crown. The periodontal space near the mesial root was widened (Figure 1).

Diagnosis:

Since there were no symptoms as well as no significant abnormalities on pulp vitality tests, the diagnosis was: reversible localized pulpitis.

Therapy:

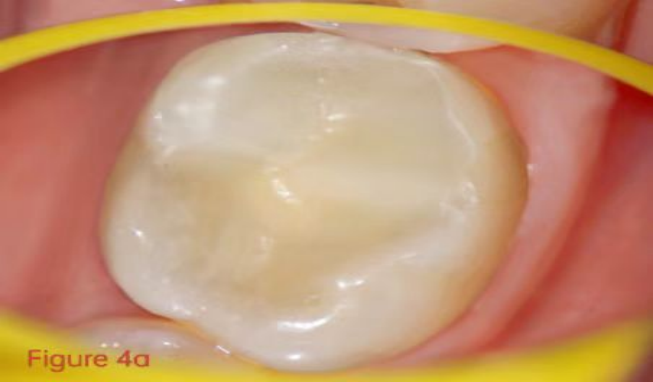

After periodontal anesthesia and wetting with a rubber barrier, the temporary sealing material and the carious softened dentin of the distal mesial cavity are removed and the gingival wall is elevated (Approximal-Box-Elevation). The pulp is exposed during the removal of carious lesions. After debridement of the pulp chamber roof and removal of the crown pulp at the root canal opening, hemostasis was performed with a cotton ball soaked in 3% sodium hypochlorite solution for 3 minutes (Fig. 2). The pulp section was covered with a hydrated calcium silicate-based cementum Biodentine (Septodont, Germany) and the pulp chamber was similarly filled with this material (Figure 3). After a 15-minute wait, the crowns were restored by the enamel-dentin acid etching bonding technique (Fig. 4a and b). Radiographs of the treated single tooth showed a well-filled distal mesial cavity margin and uniform filling within the crown (Fig. 5).

Figure 2: Clinical condition after live pulp excision and hemostasis in the upper part of the root canal opening.

Figure 3: Clinical status after capping the medulla oblongata with a hydrated calcium silicate-based salmonate.

Figure 4a and b: Conditions after restoration of clinical crowns with composite resin.

Figure 5: Dental radiographs at the end of treatment.

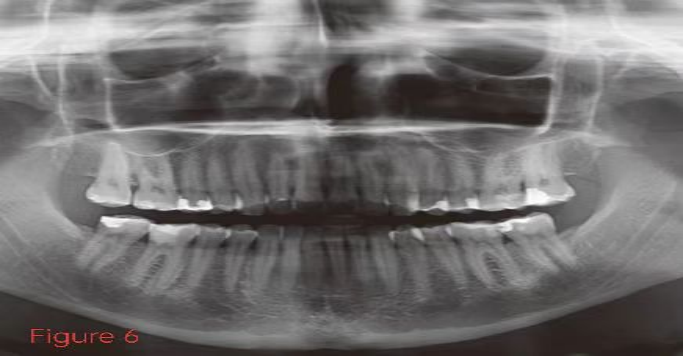

follow up medical treatment:The patients were followed up at 6 and 9 months postoperatively, respectively, and none of them had subjective symptoms. There were also no pathologic findings on clinical and imaging examinations (Figures 6 and 7). Pulp vitality testing showed that the teeth were sensitive to thermal and electrical stimuli and did not differ significantly from adjacent teeth.

Figure 6: Panoramic film used to develop the overall treatment plan and #46 3-month checkup after dental treatment.

Figure 7: X-ray 9 months after live myeloablation.

Live pulpotomy of permanent teeth was performed in the case because the pulp was penetrated during the removal of carious tissue and it was still a reversible pulpitis. The spread of inflammation was stopped by removing the affected pulp tissue. In this way the uninvolved living pulp is protected and complete root canal treatment is avoided. The difficulty with this treatment technique is mainly that the prognosis depends to a large extent on the correct assessment of the extent of the pulpal lesion. The extent to which the dentist’s experience can make a difference has not been adequately studied in the literature. Success rates of 85-97% after two years of partial pulpal severance have been reported in the literature. The success rate for total crown pulp severance varies between 75-94%. The initial examination is to determine whether it is a reversible or irreversible pulpitis. Symptomatic irreversible pulpitis is not amenable to living pulp preservation therapy because of its low success rate and questionable due to new discoveries about the restorative capacity of the pulp. If treatment fails due to pulp necrosis, the overall prognosis of the affected tooth is lower than that of pulpotomy; therefore, clinical follow-up should be performed at 3, 6, and 12 months postoperatively to critically assess the condition of the pulp and tooth. After performing pulpotomy, the distance between the remaining living pulp and the clinical crown increases, resulting in the possibility of a delayed or even negative pulpal response during pulp vitality testing. Therefore, another imaging should be done at each follow-up visit. Since infection of the root canal system may also occur years later, the affected tooth should be traced both clinically and radiographically.

If the clinical indications are correct, it is preferable to replace a complete root canal with a living pulpotomy. This treatment technique preserves the complex living pulp tissue, thus preserving the defensive and restorative capacity of the pulp as well as its signaling function. The load it can carry is also similar to that of a tooth with a healthy pulp and undamaged collagen in the root. In addition, living pulp cutting is technically simpler than the complete preparation, disinfection and filling of a root canal system.